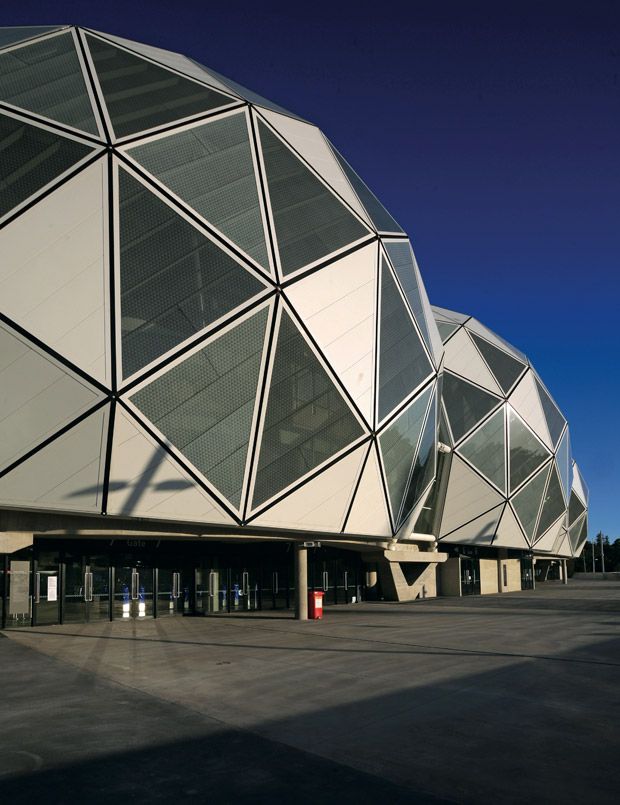

Developed by Cox and engineers ARUP, the stadium’s jewelled structural economy reflects rapidly unfolding technologies. Its designers point out that the stadium uses one-tenth the steel per seat of Beijing’s acclaimed Bird’s Nest and one-third that of Munich’s membrane-clad Allianz stadium. The stadium’s striking form has already earned it the affectionate nickname Bubble Dome.

The stadium offers a remarkable form and lightness. So much so that in a precinct bristling with sports and entertainment venues, it signals a new era of technical and creative possibilities.

The bioframe’s tour de force of stylish efficiency is partly illustrated by figures: even the lauded MCG Great Northern Stand uses 50 per cent more steel. While reduced material costs are significant, the complexity of the AAMI Park build tends to offset most of those savings, according to Cox design director Patrick Ness.

Sited in parkland on Edwin Flack reserve where sports and entertainment venues predominate, ‘Bubble Dome’ is part of a linear necklace of major civic structures. This begins at the southern, or city, end with the Arts Centre Spire (1982), Sydney Myer Music Bowl (1959), Olympic Swimming Pool (1956) and concludes with this distinctive stadium – the faceted exuberance of which is created from more than 2200 diagrid XLERPLATE® steel and glass panels.

Such a historic ‘avenue’ is more than simply built fabric.

“There is a lightness to many of those forms and that definitely guided us towards such an ephemeral result,” says Ness. “We feel privileged. You’d like to keep going on this sort of wave so we’ll see where it takes us.”

Patrick Ness, Design Director, Cox Architecture

At a glance the steelwork creates a series of what appears to be helium-filled bonnets, or a giant, looping caterpillar.

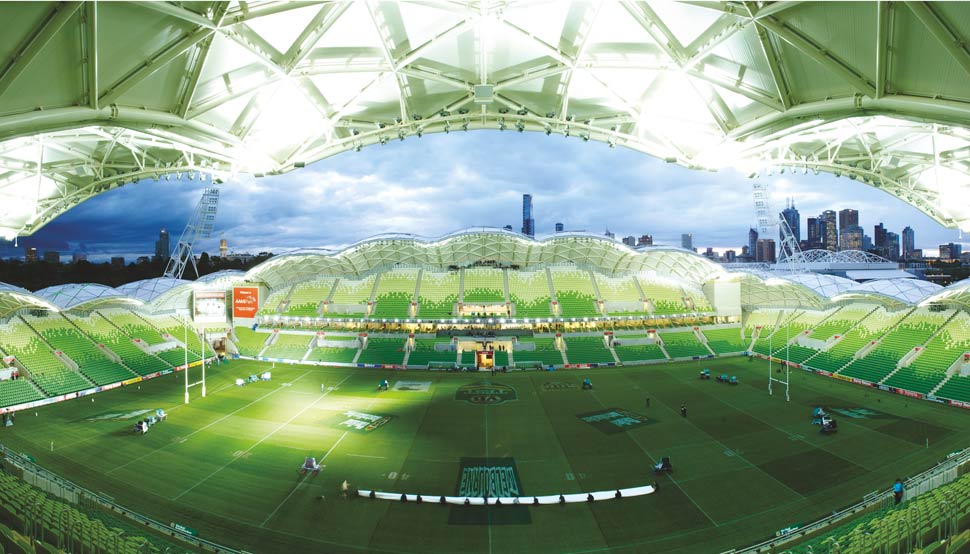

Despite the endless variations on the theme, these fully grounded bays create a strong, almost hypnotic structural rhythm. It’s also a stadium that in many ways feels bigger than its dimensions suggest. Ness attributes this ‘larger than life’ quality to the design.

“Because of its unique acoustic characteristics a crowd of 30,000 roars more like 50,000 and yet it has this wonderful sense of intimacy,” he says.

“Stadia are often grim and predictable,” Ness adds. “They lack an emotion. They don’t always concentrate the mind or crowd energy.”

Design colleague and stadium project director Jonathan Gardiner of Cox recalls the stadium’s baptism in 2010 which saw water cascade from incomplete roof gutters during a freak rainfall. Gardiner almost shivers at the recollection. “The city received one of its heaviest downpours just before and during the first half of the game.

“The building was so close, yet not quite, finished,” he explains. “There was enough guttering made from COLORBOND® steel at that time to collect the water, but not enough to carry it away.”

Ness says the structural team was ever-mindful of a sports metaphor.

“‘Further, stronger and lighter all the time’. That was our motto and steel was absolutely the right material to suit it,” he adds. “We could hone and feather it to such a minimal cross-section and achieve this exceptional lightness.”

Patrick Ness, Design Director, Cox Architecture

The stadium’s clever and intricate structure operates in three different ways: as shell, arch and cantilever. “Each structural system creates the ‘bioframe’ hybrid,” says Ness. “After we worked up the structural model with ARUP we asked: ‘What would happen in the worst-case scenario of catastrophic failure?’ We wanted to know what would happen if major support sections were removed. All of our modelling proved its unique individual and combined strength.”

Reduction in material use is now made possible by building information modelling (BIM) and computer engineering programs that allow rapid testing and refinement. “It allowed us to identify where the flow patterns were and test different loadings, so the structure is fully optimised as a result of those technologies,” Ness says.

Ness philosophically concludes that the building embodies the spirit of its intended use and this is reflected in its materials and form.

“The aim was to achieve an almost liquid shape and lightness. Steel was central to that because it allowed us to span further than with any other material,” he says. “Its parallel in sport has the same endeavour in the structure. We’re forever trying to go faster and further as human beings. Design and sport are locked in a dance and that’s what makes it so beautiful.”